Our Story

AND THIS IS HOW IT STARTED...

It was a long way from Hahira, Georgia, and his bees wouldn't be able to go with him. But Jim believed it was a tremendous opportunity, and he was intent on making the trip. It was 1972.

Jim Powers, my father-in-law, stubborn, proud, cantankerous, and one of the largest producers of honey in the United States, decided the Island of Hawaii was perfect for making honey and starting his eighth and last honey operation.

Of course, on this and on all matters concerning honey and bees, he was right. The island was immense—almost 4,000 square miles in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, larger than Connecticut. With only 65,000 inhabitants, it was pristine. And flowers everywhere, blooming year-round.

Jim's step-son and my husband, Garnett Puett, took over the Hawaiian operation in 1987 and became the fourth generation of his family to make beekeeping his livelihood. The experience gleaned from prior generations emphasized the important relationship between the environment and the bees’ well being. While maintaining our artisanal standards, the business and hives continued to flourish and grow, resulting in hundreds-of-thousands of pounds of uniquely Hawaiian honey—all of which was exported container after container to mainland honey packers.

Unfortunately, living in paradise did not protect us from global developments that were transforming the honey industry for the worse: cheap adulterated Chinese honey; global warming; and the spread of parasitic mites, all of which combined to crush honey prices and threaten our bees. We had to rethink the business model. Beginning in 2004, I started selling our honey at local farmers markets under our own label: Big Island Bees.

Because we didn't have the sophisticated packing equipment of mainland packers, I simply hand poured honey from the hives into glass jars. I didn't heat it. I didn't filter it. And it tasted wonderful!

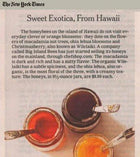

The locals loved having locally sourced honey but it was the flavor that really made them swoon—rich, velvety, dark-as-chocolate Macadamia; light, floral, delicate Lehua; and spicy, amber Christmas Berry (Wilelaiki)—each honey variety so different from one another, attributable to the type of flower from which each honey is made. This intense flavor profile is what makes our honey so unique.

We also think we are unique among beekeeping families for our appreciation and display of the bees’ artistic majesty. This artistry is most pronounced in Garnett’s apisculptures, a close collaboration between Garnett and the bees in creating beeswax sculptures which have been exhibited around the world, including New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

Our packaging is reflective of the beauty of the bees’ hives and the local environment in which they thrive.

We hope you will have a chance to visit us when you travel to Hawaii so we can show you our operations and let you sample our many honey products.

But if you have no immediate plans for a Hawaiian vacation, we hope you will consider ordering directly from us on our website. We promise it is only honey produced by our family's bees here on the Big Island, and that you will find the flavors to be unique and wonderful.

Mahalo,

Whendi

Queen Bee

VIEW US IN THE PRESS

DID YOU KNOW

Our Bees Support "Alala" Crow Conservation

The Hawaiian crow known as ‘Alala is one of the many endangered birds in Hawaii. The word “’Alala” is taken from two Hawaiian words, “ala” and “la,” which mean “to rise up” and “sun,” respectively. The crow was given this name because it makes a great noise in the morning. Its feathers are dark brown, its head and tail almost black, and its bill, legs and feet are black and iris brown. The ‘Alala soars quietly but its call sounds like a crying child. It eats the fleshy flower and fruit of the ieie vine, the ohelo berry, and other berries in the forests.

Prior to the 1890s, the ‘Alala crow flourished. But, in the decades following, flocks disappeared, due to habitat loss and poultry farmers who saw the crows as a nuisance and hunted them down. Only solitary birds remained. Now there are less than thirty ‘Alala left in Hawaii (15 in captivity and 14 in the wild). Despite the grim numbers, the ‘Alala still has a chance!

Today, people are taking action. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service supports a captive breeding facility. The Hawaii Audubon society is trying to stop owners of the Big Island ranch from logging koa trees. And, about 10 years ago, we began supplying bee larvae to the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center in the town of Volcano, near Kilauea. The ‘Alala babies love eating our bee larvae!